|

HOW TO DO

IT? A DIFFERENT WAY OF ORGANIZING THE GOVERNMENT

As pre se ntly configure

d, the national security institutions of the U.S. government are still

the institutions constructed to win the Cold War. The United States

confronts a very different world today. Instead of facing a few very

dangerous adversaries, the United States confronts a number of less

visi- ble challenges that surpass the boundaries of traditional

nation-states and call for quick, imaginative, and agile responses.

The men and women of theWorldWar II generation rose to the challenges of

the 1940s and 1950s.They restructured the government so that it could

protect the country. That is now the job of the generation that

experienced 9/11. Those attacks showed, emphatically, that ways of doing

business rooted in a dif- ferent era are just not good enough. Americans

should not settle for incremen- tal, ad hoc adjustments to a system

designed generations ago for a world that no longer exists.

We recommend significant changes in the organization of the government.

We know that the quality of the people is more important than the

quality of the wiring diagrams. Some of the saddest aspects of the 9/11

story are the out- standing efforts of so many individual officials

straining, often without success, against the boundaries of the

possible. Good people can overcome bad struc- tures.They should not have

to.

The United States has the resources and the people.The government should

combine them more effectively, achieving unity of effort.We offer five

major

recommendations to do that:

o unifying strategic

intelligence and operational planning against

Islamist terrorists across the foreign-domestic divide with a National

Counterterrorism Center;

o unifying the intelligence community with a new National Intelli-

gence Director;

399

400 THE 9/11 COMMISSION

REPORT

o unifying the many

participants in the counterterrorism effort and

their knowledge in a network-based information-sharing system that

transcends traditional governmental boundaries;

o unifying and strengthening congressional oversight to improve qual-

ity and accountability; and

o strengthening the FBI and homeland defenders.

13.1 UNITY OF EFFORT

ACROSS THE

FOREIGN-DOMESTIC DIVIDE

Joint Action

Much of the public commentary about the 9/11 attacks has dealt with

"lost opportunities," some of which we reviewed in chapter 11.These are

often char- acterized as problems of "watchlisting," of "information

sharing," or of "con- necting the dots." In chapter 11 we explained that

these labels are too narrow. They describe the symptoms, not the

disease.

In each of our examples, no one was firmly in charge of managing the

case and able to draw relevant intelligence from anywhere in the

government, assign responsibilities across the agencies (foreign or

domestic), track progress, and quickly bring obstacles up to the level

where they could be resolved. Respon- sibility and accountability were

diffuse.

The agencies cooperated, some of the time. But even such cooperation as

there was is not the same thing as joint action.When agencies cooperate,

one defines the problem and seeks help with it.When they act jointly,

the problem and options for action are defined differently from the

start. Individuals from different backgrounds come together in analyzing

a case and planning how to manage it.

In our hearings we regularly asked witnesses:Who is the quarterback? The

other players are in their positions, doing their jobs. But who is

calling the play

that assigns roles to help them execute as a team?

Since 9/11, those issues have not been resolved. In some ways joint work

has gotten better, and in some ways worse.The effort of fighting

terrorism has flooded over many of the usual agency boundaries because

of its sheer quan- tity and energy. Attitudes have changed. Officials

are keenly conscious of try- ing to avoid the mistakes of 9/11. They try

to share information. They circulate-even to the President-practically

every reported threat, however dubious.

Partly because of all this effort, the challenge of coordinating it has

multi- plied. Before 9/11, the CIA was plainly the lead agency

confronting al Qaeda. The FBI played a very secondary role.The

engagement of the departments of Defense and State was more episodic.

HOW TO DO IT? 401

o Today the CIA is still

central. But the FBI is much more active, along

with other parts of the Justice Department.

o The Defense Department effort is now enormous.Three of its uni-

fied commands, each headed by a four-star general, have counterter-

rorism as a primary mission: Special Operations Command, Central Command

(both headquartered in Florida), and Northern Command (headquartered in

Colorado).

o A new Department of Homeland Security combines formidable

resources in border and transportation security, along with analysis of

domestic vulnerability and other tasks.

o The State Department has the lead on many of the foreign policy tasks

we described in chapter 12.

o At the White House, the National Security Council (NSC) now is

joined by a parallel presidential advisory structure, the Homeland

Security Council.

So far we have mentioned

two reasons for joint action-the virtue of joint planning and the

advantage of having someone in charge to ensure a unified effort.There

is a third: the simple shortage of experts with sufficient skills.The

limited pool of critical experts-for example, skilled counterterrorism

analysts and linguists-is being depleted. Expanding these capabilities

will require not just money, but time.

Primary responsibility for terrorism analysis has been assigned to the

Ter- rorist Threat Integration Center (TTIC), created in 2003, based at

the CIA headquarters but staffed with representatives of many agencies,

reporting directly to the Director of Central Intelligence.Yet the CIA

houses another intelligence "fusion" center: the Counterterrorist Center

that played such a key role before 9/11.A third major analytic unit is

at Defense, in the Defense Intelligence Agency. A fourth, concentrating

more on homeland vulnerabili- ties, is at the Department of Homeland

Security.The FBI is in the process of building the analytic capability

it has long lacked, and it also has the Terrorist

Screening Center.1

The U.S. government cannot afford so much duplication of effort.There

are not enough experienced experts to go around.The duplication also

places extra demands on already hard-pressed single-source national

technical intelligence collectors like the National Security Agency.

Combining Joint

Intelligence and Joint Action

A"smart"government would integrate all sources of information to see the

enemy as a whole. Integrated all-source analysis should also inform and

shape strategies to collect more intelligence.Yet the Terrorist Threat

Integration Center, while it has primary responsibility for terrorism

analysis, is formally proscribed from hav-

402 THE 9/11 COMMISSION

REPORT

ing any oversight or

operational authority and is not part of any operational

entity, other than reporting to the director of central intelligence.2

The government now tries to handle the problem of joint management,

informed by analysis of intelligence from all sources, in two ways.

o First, agencies with

lead responsibility for certain problems have con-

structed their own interagency entities and task forces in order to get

cooperation. The Counterterrorist Center at CIA, for example, recruits

liaison officers from throughout the intelligence community. The

military's Central Command has its own interagency center, recruiting

liaison officers from all the agencies from which it might need help.The

FBI has Joint Terrorism Task Forces in 84 locations to coordinate the

activities of other agencies when action may be required.

o Second, the problem of joint operational planning is often passed to

the White House, where the NSC staff tries to play this role. The

national security staff at theWhite House (both NSC and new Home- land

Security Council staff) has already become 50 percent larger since 9/11.

But our impression, after talking to serving officials, is that even

this enlarged staff is consumed by meetings on day-to-day issues, sift-

ing each day's threat information and trying to coordinate everyday

operations.

Even as it crowds into

every square inch of available office space, the NSC staff is still not

sized or funded to be an executive agency. In chapter 3 we described

some of the problems that arose in the 1980s when a White House staff,

constitutionally insulated from the usual mechanisms of oversight,

became involved in direct operations. During the 1990s Richard Clarke

occa- sionally tried to exercise such authority, sometimes successfully,

but often caus- ing friction.

Yet a subtler and more serious danger is that as the NSC staff is

consumed by these day-to-day tasks, it has less capacity to find the

time and detachment needed to advise a president on larger policy

issues. That means less time to work on major new initiatives, help with

legislative management to steer needed bills through Congress, and track

the design and implementation of the strategic plans for regions,

countries, and issues that we discuss in chapter 12.

Much of the job of operational coordination remains with the agencies,

especially the CIA.There DCI Tenet and his chief aides ran interagency

meet- ings nearly every day to coordinate much of the government's

day-to-day work.The DCI insisted he did not make policy and only oversaw

its imple- mentation. In the struggle against terrorism these

distinctions seem increasingly artificial. Also, as the DCI becomes a

lead coordinator of the government's

HOW TO DO IT? 403

operations, it becomes

harder to play all the position's other roles, including that of analyst

in chief.

The problem is nearly intractable because of the way the government is

cur- rently structured. Lines of operational authority run to the

expanding execu- tive departments, and they are guarded for

understandable reasons: the DCI commands the CIA's personnel overseas;

the secretary of defense will not yield to others in conveying commands

to military forces; the Justice Department will not give up the

responsibility of deciding whether to seek arrest warrants. But the

result is that each agency or department needs its own intelligence

apparatus to support the performance of its duties. It is hard to "break

down stovepipes" when there are so many stoves that are legally and

politically enti- tled to have cast-iron pipes of their own.

Recalling the Goldwater-Nichols legislation of 1986, Secretary Rumsfeld

reminded us that to achieve better joint capability, each of the armed

services had to "give up some of their turf and authorities and

prerogatives."Today, he said, the executive branch is "stove-piped much

like the four services were nearly 20 years ago." He wondered if it

might be appropriate to ask agencies to "give up some of their existing

turf and authority in exchange for a stronger, faster, more efficient

government wide joint effort."3 Privately, other key offi- cials have

made the same point to us.

We therefore propose a new institution: a civilian-led unified joint

com- mand for counterterrorism. It should combine strategic intelligence

and joint operational planning.

In the Pentagon's Joint Staff, which serves the chairman of the Joint

Chiefs of Staff, intelligence is handled by the J-2 directorate,

operational planning by J-3, and overall policy by J-5. Our concept

combines the J-2 and J-3 functions (intelligence and operational

planning) in one agency, keeping overall policy coordination where it

belongs, in the National Security Council.

Recommendation: We

recommend the establishment of a National Counterterrorism Center

(NCTC), built on the foundation of the existing Terrorist Threat

Integration Center (TTIC). Breaking the older mold of national

government organization, this NCTC should be a center for joint

operational planning and joint intelligence, staffed by personnel from

the various agencies. The head of the NCTC should have authority to

evaluate the performance of the people assigned to the Center.

o Such a joint center

should be developed in the same spirit that guided

the military's creation of unified joint commands, or the shaping of

earlier national agencies like the National Reconnaissance Office, which

was formed to organize the work of the CIA and several defense agencies

in space.

404

THE 9/11 COMMISSION

REPORT

NCTC-Intelligence. The

NCTC should lead strategic analysis, pooling all-source intelligence,

foreign and domestic, about transna- tional terrorist organizations with

global reach. It should develop net assessments (comparing enemy

capabilities and intentions against U.S. defenses and countermeasures).

It should also provide warning. It should do this work by drawing on the

efforts of the CIA, FBI, Homeland Security, and other departments and

agencies. It should task collection requirements both inside and outside

the United States.

o The intelligence

function (J-2) should build on the existing TTIC

structure and remain distinct, as a national intelligence center, within

the NCTC. As the government's principal knowledge bank on Islamist

terrorism,with the main responsibility for strategic analysis and net

assessment, it should absorb a significant portion of the analytical

talent now residing in the CIA's Counterterrorist Center and the DIA's

Joint Intelligence Task Force-Combatting Terrorism (JITF-CT).

NCTC-Operations. The NCTC should perform joint planning.

The plans would assign operational responsibilities to lead agencies,

such as State, the CIA, the FBI, Defense and its combatant commands,

Homeland Security, and other agencies.The NCTC should not direct the

actual execution of these operations, leaving that job to the agen-

cies. The NCTC would then track implementation; it would look across the

foreign-domestic divide and across agency boundaries,

updating plans to follow through on cases.4

o The joint operational planning function (J-3) will be new to theTTIC

structure.The NCTC can draw on analogous work now being done in the CIA

and every other involved department of the government, as well as

reaching out to knowledgeable officials in state and local agencies

throughout the United States.

o The NCTC should not be a policymaking body. Its operations and

planning should follow the policy direction of the president and the

National Security Council.

Consider this

hypothetical case.The NSA discovers that a suspected ter- rorist is

traveling to Bangkok and Kuala Lumpur. The NCTC should draw on joint

intelligence resources, including its own NSA counter- terrorism

experts, to analyze the identities and possible destinations of

HOW TO DO IT? 405

these individuals.

Informed by this analysis, the NCTC would then organize and plan the

management of the case, drawing on the talents and differing kinds of

experience among the several agency represen- tatives assigned to

it-assigning tasks to the CIA overseas, to Homeland Security watching

entry points into the United States, and to the FBI. If military

assistance might be needed, the Special Operations Com- mand could be

asked to develop an appropriate concept for such an operation.The NCTC

would be accountable for tracking the progress of the case, ensuring

that the plan evolved with it, and integrating the information into a

warning.The NCTC would be responsible for being sure that intelligence

gathered from the activities in the field became part of the

government's institutional memory about Islamist terrorist

personalities, organizations, and possible means of attack.

In each case the involved agency would make its own senior man- agers

aware of what it was being asked to do. If those agency heads objected,

and the issue could not easily be resolved, then the disagree- ment

about roles and missions could be brought before the National Security

Council and the president.

NCTC-Authorities. The

head of the NCTC should be appointed by the

president, and should be equivalent in rank to a deputy head of a

cabinet department.The head of the NCTC would report to the national

intelligence director, an office whose creation we recommend below,

placed in the Exec- utive Office of the President.The head of the NCTC

would thus also report indirectly to the president.This official's

nomination should be confirmed by the Senate and he or she should

testify to the Congress, as is the case now with other statutory

presidential offices, like the U.S. trade representative.

o To avoid the fate of

other entities with great nominal authority and

little real power, the head of the NCTC must have the right to con- cur

in the choices of personnel to lead the operating entities of the

departments and agencies focused on counterterrorism, specifically

including the head of the Counterterrorist Center, the head of the FBI's

Counterterrorism Division, the commanders of the Defense Department's

Special Operations Command and Northern Com- mand, and the State

Department's coordinator for counterterrorism.5 The head of the NCTC

should also work with the director of the Office of Management and

Budget in developing the president's counterterrorism budget.

406 THE 9/11 COMMISSION

REPORT

o There are precedents

for surrendering authority for joint planning

while preserving an agency's operational control. In the international

context, NATO commanders may get line authority over forces assigned by

other nations. In U.S. unified commands, commanders plan operations that

may involve units belonging to one of the serv- ices. In each case,

procedures are worked out, formal and informal, to define the limits of

the joint commander's authority.

The most serious

disadvantage of the NCTC is the reverse of its greatest virtue. The

struggle against Islamist terrorism is so important that any clear-cut

cen- tralization of authority to manage and be accountable for it may

concentrate too much power in one place. The proposed NCTC would be

given the authority of planning the activities of other agencies. Law or

executive order must define the scope of such line authority.

The NCTC would not eliminate interagency policy disputes.These would

still go to the National Security Council.To improve coordination at

theWhite House, we believe the existing Homeland Security Council should

soon be merged into a single National Security Council.The creation of

the NCTC should help the NSC staff concentrate on its core duties of

assisting the pres- ident and supporting interdepartmental policymaking.

We recognize that this is a new and difficult idea precisely because the

authorities we recommend for the NCTC really would, as Secretary Rums-

feld foresaw, ask strong agencies to "give up some of their turf and

authority in exchange for a stronger, faster, more efficient government

wide joint effort." Countering transnational Islamist terrorism will

test whether the U.S. govern- ment can fashion more flexible models of

management needed to deal with the twenty-first-century world.

An argument against change is that the nation is at war, and cannot

afford to reorganize in midstream. But some of the main innovations of

the 1940s and 1950s, including the creation of the Joint Chiefs of Staff

and even the construc- tion of the Pentagon itself, were undertaken in

the midst of war. Surely the country cannot wait until the struggle

against Islamist terrorism is over.

"Surprise, when it happens to a government, is likely to be a

complicated, diffuse, bureaucratic thing. It includes neglect of

responsibility, but also respon- sibility so poorly defined or so

ambiguously delegated that action gets lost."6 That comment was made

more than 40 years ago, about Pearl Harbor.We hope another commission,

writing in the future about another attack, does not again find this

quotation to be so apt.

HOW TO DO IT? 407

13.2 UNITY OF EFFORT IN

THE

INTELLIGENCE COMMUNITY

In our first section, we

concentrated on counterterrorism, discussing how to combine the analysis

of information from all sources of intelligence with the joint planning

of operations that draw on that analysis. In this section, we step back

from looking just at the counterterrorism problem. We reflect on whether

the government is organized adequately to direct resources and build the

intelligence capabilities it will need not just for countering

terrorism, but for the broader range of national security challenges in

the decades ahead.

The Need for a Change

During the Cold War, intelligence agencies did not depend on seamless

inte- gration to track and count the thousands of military targets-such

as tanks and missiles-fielded by the Soviet Union and other adversary

states. Each agency concentrated on its specialized mission, acquiring

its own information and then sharing it via formal, finished reports.The

Department of Defense had given birth to and dominated the main agencies

for technical collection of intelli- gence. Resources were shifted at an

incremental pace, coping with challenges that arose over years, even

decades.

We summarized the resulting organization of the intelligence community

in chapter 3. It is outlined below.

Members of the U.S.

Intelligence Community

Office of the Director of Central Intelligence, which includes the

Office of the Deputy Director of Central Intelligence for Community Man-

agement, the Community Management Staff, theTerrorismThreat Inte-

gration Center, the National Intelligence Council, and other

community offices

The Central Intelligence

Agency (CIA), which performs human source

collection, all-source analysis, and advanced science and technology

National intelligence

agencies:

o National Security Agency (NSA), which performs signals

collection and analysis

o National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency (NGA), which

performs imagery collection and analysis

408 THE 9/11 COMMISSION

REPORT

o National Reconnaissance

Office (NRO), which develops,

acquires,and launches space systems for intelligence collection

o Other national reconnaissance programs

Departmental intelligence

agencies:

o Defense Intelligence Agency (DIA) of the Department of

Defense

o Intelligence entities of the Army, Navy, Air Force, and

Marines

o Bureau of Intelligence and Research (INR) of the Depart-

ment of State

o Office of Terrorism and Finance Intelligence of the Depart-

ment of Treasury

o Office of Intelligence and the Counterterrorism and Coun-

terintelligence Divisions of the Federal Bureau of Investiga-

tion of the Department of Justice

o Office of Intelligence of the Department of Energy

o Directorate of Information Analysis and Infrastructure Pro-

tection (IAIP) and Directorate of Coast Guard Intelligence

of the Department of Homeland Security

The need to restructure

the intelligence community grows out of six prob-

lems that have become apparent before and after 9/11:

o Structural barriers to

performing joint intelligence work. National intelli-

gence is still organized around the collection disciplines of the home

agencies, not the joint mission. The importance of integrated, all-

source analysis cannot be overstated.Without it, it is not possible to

"connect the dots." No one component holds all the relevant infor-

mation.

By contrast, in organizing national defense, the Goldwater- Nichols

legislation of 1986 created joint commands for operations in the field,

the Unified Command Plan.The services-the Army, Navy, Air Force, and

Marine Corps-organize, train, and equip their peo- ple and units to

perform their missions. Then they assign personnel and units to the

joint combatant commander, like the commanding general of the Central

Command (CENTCOM). The Goldwater- Nichols Act required officers to serve

tours outside their service in order to win promotion.The culture of the

Defense Department was

HOW TO DO IT? 409

transformed, its

collective mind-set moved from service-specific to

"joint," and its operations became more integrated.7

o Lack of common standards and practices across the foreign-domestic

divide.The

leadership of the intelligence community should be able to pool infor-

mation gathered overseas with information gathered in the United States,

holding the work-wherever it is done-to a common stan- dard of quality

in how it is collected, processed (e.g., translated), reported, shared,

and analyzed. A common set of personnel standards for intelligence can

create a group of professionals better able to oper- ate in joint

activities,transcending their own service-specific mind-sets.

o Divided management of national intelligence capabilities. While the

CIA

was once "central" to our national intelligence capabilities, following

the end of the Cold War it has been less able to influence the use of

the nation's imagery and signals intelligence capabilities in three

national agencies housed within the Department of Defense: the National

Security Agency, the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency, and the

National Reconnaissance Office. One of the lessons learned from the 1991

Gulf War was the value of national intelligence systems (satellites in

particular) in precision warfare. Since that war, the department has

appropriately drawn these agencies into its trans- formation of the

military. Helping to orchestrate this transformation is the under

secretary of defense for intelligence, a position established by

Congress after 9/11. An unintended consequence of these devel- opments

has been the far greater demand made by Defense on tech- nical systems,

leaving the DCI less able to influence how these technical resources are

allocated and used.

o Weak capacity to set priorities and move resources.The agencies are

mainly

organized around what they collect or the way they collect it. But the

priorities for collection are national. As the DCI makes hard choices

about moving resources, he or she must have the power to reach across

agencies and reallocate effort.

o Too many jobs.The DCI now has at least three jobs. He is expected to

run a particular agency, the CIA. He is expected to manage the loose

confederation of agencies that is the intelligence community. He is

expected to be the analyst in chief for the government, sifting evi-

dence and directly briefing the President as his principal intelligence

adviser. No recent DCI has been able to do all three effectively. Usu-

ally what loses out is management of the intelligence community, a

difficult task even in the best case because the DCI's current author-

ities are weak.With so much to do, the DCI often has not used even the

authority he has.

410 THE 9/11 COMMISSION

REPORT

o Too complex and secret.

Over the decades, the agencies and the rules sur-

rounding the intelligence community have accumulated to a depth that

practically defies public comprehension.There are now 15 agen- cies or

parts of agencies in the intelligence community.The commu- nity and the

DCI's authorities have become arcane matters, understood only by

initiates after long study. Even the most basic information about how

much money is actually allocated to or within the intelligence community

and most of its key components is shrouded from public view.

The current DCI is

responsible for community performance but lacks the three authorities

critical for any agency head or chief executive officer: (1) control

over purse strings, (2) the ability to hire or fire senior managers, and

(3) the

ability to set standards for the information infrastructure and

personnel.8

The only budget power of the DCI over agencies other than the CIA lies

in coordinating the budget requests of the various intelligence agencies

into a single program for submission to Congress.The overall funding

request of the 15 intelligence entities in this program is then

presented to the president and Congress in 15 separate volumes.

When Congress passes an appropriations bill to allocate money to

intelli- gence agencies, most of their funding is hidden in the Defense

Department in order to keep intelligence spending secret.Therefore,

although the House and Senate Intelligence committees are the

authorizing committees for funding of the intelligence community, the

final budget review is handled in the Defense Subcommittee of the

Appropriations committees.Those committees have no subcommittees just

for intelligence, and only a few members and staff review the requests.

The appropriations for the CIA and the national intelligence agencies-

NSA, NGA, and NRO-are then given to the secretary of defense.The sec-

retary transfers the CIA's money to the DCI but disburses the national

agencies' money directly. Money for the FBI's national security

components falls within the appropriations for Commerce, Justice, and

State and goes to the

attorney general.9

In addition,the DCI lacks hire-and-fire authority over most of the

intelligence community's senior managers. For the national intelligence

agencies housed in the Defense Department, the secretary of defense must

seek the DCI's concur- rence regarding the nomination of these

directors, who are presidentially appointed.But the secretary may submit

recommendations to the president with- out receiving this

concurrence.The DCI cannot fire these officials.The DCI has even less

influence over the head of the FBI's national security component, who

is appointed by the attorney general in consultation with the DCI.10

HOW TO DO IT? 411

Combining Joint Work with

Stronger Management

We have received recommendations on the topic of intelligence reform

from many sources. Other commissions have been over this same

ground.Thought- ful bills have been introduced, most recently a bill by

the chairman of the House Intelligence Committee Porter Goss (R-Fla.),

and another by the rank- ing minority member, Jane Harman (D-Calif.). In

the Senate, Senators Bob Graham (D-Fla.) and Dianne Feinstein (D-Calif.)

have introduced reform pro- posals as well. Past efforts have foundered,

because the president did not sup- port them; because the DCI, the

secretary of defense, or both opposed them; and because some proposals

lacked merit.We have tried to take stock of these experiences, and

borrow from strong elements in many of the ideas that have already been

developed by others.

Recommendation:The

current position of Director of Central Intel- ligence should be

replaced by a National Intelligence Director with two main areas of

responsibility: (1) to oversee national intelligence centers on specific

subjects of interest across the U.S. government and (2) to manage the

national intelligence program and oversee the agencies that contribute

to it.

First, the National

Intelligence Director should oversee national intelligence centers to

provide all-source analysis and plan intelligence operations for the

whole government on major problems.

o One such problem is

counterterrorism. In this case, we believe that

the center should be the intelligence entity (formerly TTIC) inside the

National Counterterrorism Center we have proposed. It would sit there

alongside the operations management unit we described ear- lier, with

both making up the NCTC, in the Executive Office of the President. Other

national intelligence centers-for instance, on counterproliferation,

crime and narcotics, and China-would be

housed in whatever department or agency is best suited for them.

o The National Intelligence Director would retain the present DCI's

role as the principal intelligence adviser to the president.We hope the

president will come to look directly to the directors of the national

intelligence centers to provide all-source analysis in their areas of

responsibility, balancing the advice of these intelligence chiefs

against the contrasting viewpoints that may be offered by department

heads

at State, Defense, Homeland Security, Justice, and other agencies.

412 THE 9/11 COMMISSION

REPORT

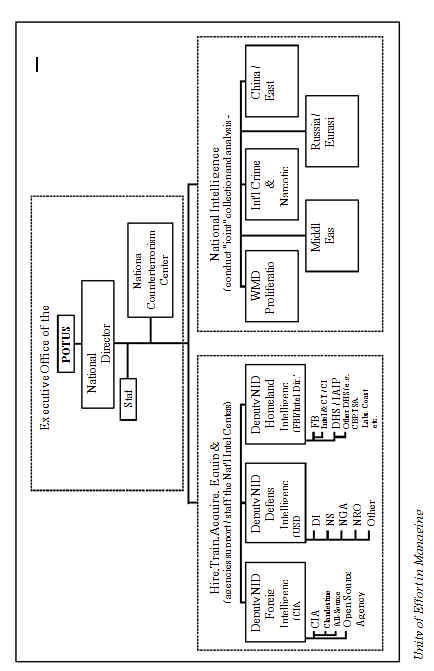

Second, the National

Intelligence Director should manage the national intelligence program

and oversee the component agencies of the intelligence

community. (See diagram.)11

o The National Intelligence Director would submit a unified budget for

national intelligence that reflects priorities chosen by the National

Security Council, an appropriate balance among the varieties of tech-

nical and human intelligence collection, and analysis. He or she would

receive an appropriation for national intelligence and apportion the

funds to the appropriate agencies, in line with that budget, and with

authority to reprogram funds among the national intelligence agen- cies

to meet any new priority (as counterterrorism was in the 1990s). The

National Intelligence Director should approve and submit nom- inations

to the president of the individuals who would lead the CIA, DIA, FBI

Intelligence Office, NSA, NGA, NRO, Information Analy- sis and

Infrastructure Protection Directorate of the Department of

Homeland Security, and other national intelligence capabilities.12

o The National Intelligence Director would manage this national effort

with the help of three deputies, each of whom would also hold a key

position in one of the component agencies.13

o foreign intelligence (the head of the CIA)

o defense intelligence (the under secretary of defense for intelli-

gence)14

o homeland intelligence (the FBI's executive assistant director for

intelligence or the under secretary of homeland security for

information analysis and infrastructure protection)

Other agencies in the intelligence community would coordinate their work

within each of these three areas, largely staying housed in the same

departments or agencies that support them now.

Returning to the analogy of the Defense Department's organiza- tion,

these three deputies-like the leaders of the Army, Navy, Air Force, or

Marines-would have the job of acquiring the systems, training the

people, and executing the operations planned by the national

intelligence centers.

And, just as the combatant commanders also report to the secre- tary of

defense, the directors of the national intelligence centers-e.g., for

counterproliferation, crime and narcotics, and the rest-also would

report to the National Intelligence Director.

o The Defense Department's military intelligence programs-the joint

military intelligence program (JMIP) and the tactical intelligence and

related activities program (TIARA)-would remain part of that

department's responsibility.

414 THE 9/11 COMMISSION REPORT

o The National

Intelligence Director would set personnel policies to

establish standards for education and training and facilitate

assignments at the national intelligence centers and across agency

lines. The National Intelligence Director also would set information

sharing and information technology policies to maximize data sharing, as

well as policies to protect the security of information.

o Too many agencies now have an opportunity to say no to change.The

National Intelligence Director should participate in an NSC execu- tive

committee that can resolve differences in priorities among the agencies

and bring the major disputes to the president for decision.

The National Intelligence

Director should be located in the Executive Office of the President.

This official, who would be confirmed by the Senate and would testify

before Congress, would have a relatively small staff of several hun-

dred people, taking the place of the existing community management

offices housed at the CIA.

In managing the whole community,the National Intelligence Director is

still providing a service function.With the partial exception of his or

her responsi- bilities for overseeing the NCTC, the National

Intelligence Director should support the consumers of national

intelligence-the president and policymak- ing advisers such as the

secretaries of state, defense, and homeland security and the attorney

general.

We are wary of too easily equating government management problems with

those of the private sector. But we have noticed that some very large

private firms rely on a powerful CEO who has significant control over

how money is spent and can hire or fire leaders of the major divisions,

assisted by a relatively modest staff,while leaving responsibility for

execution in the operating divisions.

There are disadvantages to separating the position of National

Intelligence Director from the job of heading the CIA. For example, the

National Intelli- gence Director will not head a major agency of his or

her own and may have a weaker base of support. But we believe that these

disadvantages are out-

weighed by several other considerations:

o The National

Intelligence Director must be able to directly oversee intel-

ligence collection inside the United States.Yet law and custom has coun-

seled against giving such a plain domestic role to the head of the CIA.

o The CIA will be one among several claimants for funds in setting

national priorities.The National Intelligence Director should not be

both one of the advocates and the judge of them all.

o Covert operations tend to be highly tactical, requiring close

attention.

The National Intelligence Director should rely on the relevant joint

HOW TO DO IT? 415

mission center to oversee

these details, helping to coordinate closely with theWhite House.The CIA

will be able to concentrate on build- ing the capabilities to carry out

such operations and on providing the personnel who will be directing and

executing such operations in the field.

o Rebuilding the analytic and human intelligence collection capabili-

ties of the CIA should be a full-time effort, and the director of the

CIA should focus on extending its comparative advantages.

Recommendation: The CIA

Director should emphasize (a) rebuild- ing the CIA's analytic

capabilities; (b) transforming the clandestine service by building its

human intelligence capabilities; (c) developing a stronger language

program, with high standards and sufficient financial incentives; (d)

renewing emphasis on recruiting diversity among operations officers so

they can blend more easily in foreign cities; (e) ensuring a seamless

relationship between human source col- lection and signals collection at

the operational level; and (f) stress- ing a better balance between

unilateral and liaison operations.

The CIA should retain

responsibility for the direction and execution of clan- destine and

covert operations, as assigned by the relevant national intelligence

center and authorized by the National Intelligence Director and the

president. This would include propaganda, renditions, and nonmilitary

disruption. We

believe, however, that one important area of responsibility should

change.

Recommendation: Lead

responsibility for directing and executing paramilitary operations,

whether clandestine or covert, should shift to the Defense

Department.There it should be consolidated with the capabilities for

training, direction, and execution of such operations already being

developed in the Special Operations Command.

o Before 9/11, the CIA

did not invest in developing a robust capability

to conduct paramilitary operations with U.S. personnel. It relied on

proxies instead, organized by CIA operatives without the requisite

military training.The results were unsatisfactory.

o Whether the price is measured in either money or people, the United

States cannot afford to build two separate capabilities for carrying out

secret military operations, secretly operating standoff missiles, and

secretly training foreign military or paramilitary forces. The United

States should concentrate responsibility and necessary legal authori-

ties in one entity.

416 THE 9/11 COMMISSION

REPORT

o The post-9/11

Afghanistan precedent of using joint CIA-military

teams for covert and clandestine operations was a good one. We believe

this proposal to be consistent with it. Each agency would con- centrate

on its comparative advantages in building capabilities for joint

missions.The operation itself would be planned in common.

o The CIA has a reputation for agility in operations.The military has a

reputation for being methodical and cumbersome.We do not know if these

stereotypes match current reality; they may also be one more symptom of

the civil-military misunderstandings we described in chapter 4. It is a

problem to be resolved in policy guidance and agency management, not in

the creation of redundant, overlapping capabili- ties and authorities in

such sensitive work.The CIA's experts should be integrated into the

military's training, exercises, and planning. To quote a CIA official

now serving in the field:"One fight, one team."

Recommendation: Finally,

to combat the secrecy and complexity we have described, the overall

amounts of money being appropriated for national intelligence and to its

component agencies should no longer be kept secret. Congress should pass

a separate appropriations act for intelligence, defending the broad

allocation of how these tens of bil- lions of dollars have been assigned

among the varieties of intelligence work.

The specifics of the

intelligence appropriation would remain classified, as they are today.

Opponents of declassification argue that America's enemies could learn

about intelligence capabilities by tracking the top-line appropria-

tions figure.Yet the top-line figure by itself provides little insight

into U.S. intel- ligence sources and methods. The U.S. government

readily provides copious information about spending on its military

forces, including military intelli- gence.The intelligence community

should not be subject to that much disclo- sure. But when even aggregate

categorical numbers remain hidden, it is hard to judge priorities and

foster accountability.

13.3 UNITY OF EFFORT IN

SHARING INFORMATION

Information Sharing

We have already stressed the importance of intelligence analysis that

can draw on all relevant sources of information. The biggest impediment

to all-source analysis-to a greater likelihood of connecting the dots-is

the human or sys- temic resistance to sharing information.

The U.S. government has access to a vast amount of information. When

databases not usually thought of as "intelligence," such as customs or

immigra-

HOW TO DO IT? 417

tion information, are

included, the storehouse is immense. But the U.S. gov- ernment has a

weak system for processing and using what it has. In interviews around

the government, official after official urged us to call attention to

frus- trations with the unglamorous "back office" side of government

operations.

In the 9/11 story, for example, we sometimes see examples of information

that could be accessed-like the undistributed NSA information that would

have helped identify Nawaf al Hazmi in January 2000. But someone had to

ask for it. In that case, no one did. Or, as in the episodes we describe

in chapter 8, the information is distributed, but in a compartmented

channel. Or the infor- mation is available, and someone does ask, but it

cannot be shared.

What all these stories have in common is a system that requires a demon-

strated "need to know" before sharing.This approach assumes it is

possible to know, in advance, who will need to use the information. Such

a system implic- itly assumes that the risk of inadvertent disclosure

outweighs the benefits of wider sharing.Those ColdWar assumptions are no

longer appropriate.The cul- ture of agencies feeling they own the

information they gathered at taxpayer expense must be replaced by a

culture in which the agencies instead feel they have a duty to the

information-to repay the taxpayers' investment by making that

information available.

Each intelligence agency has its own security practices, outgrowths of

the Cold War.We certainly understand the reason for these practices.

Counterin- telligence concerns are still real, even if the old Soviet

enemy has been replaced by other spies.

But the security concerns need to be weighed against the costs. Current

security requirements nurture overclassification and excessive

compartmenta- tion of information among agencies. Each agency's

incentive structure opposes sharing, with risks (criminal, civil, and

internal administrative sanctions) but few rewards for sharing

information. No one has to pay the long-term costs of over- classifying

information, though these costs-even in literal financial terms- are

substantial.There are no punishments for not sharing

information.Agencies uphold a "need-to-know" culture of information

protection rather than pro-

moting a "need-to-share" culture of integration.15

Recommendation:

Information procedures should provide incentives for sharing, to restore

a better balance between security and shared knowledge.

Intelligence gathered

about transnational terrorism should be processed, turned into reports,

and distributed according to the same quality standards, whether it is

collected in Pakistan or in Texas.

The logical objection is that sources and methods may vary greatly in

dif- ferent locations.We therefore propose that when a report is first

created, its data be separated from the sources and methods by which

they are obtained.The

418 THE 9/11 COMMISSION

REPORT

report should begin with

the information in its most shareable, but still mean- ingful, form.

Therefore the maximum number of recipients can access some form of that

information. If knowledge of further details becomes important, any user

can query further, with access granted or denied according to the rules

set for the network-and with queries leaving an audit trail in order to

deter- mine who accessed the information. But the questions may not come

at all unless experts at the "edge" of the network can readily discover

the clues that

prompt to them.16

We propose that information be shared horizontally, across new networks

that transcend individual agencies.

o The current system is

structured on an old mainframe, or hub-and-

spoke, concept. In this older approach, each agency has its own data-

base. Agency users send information to the database and then can

retrieve it from the database.

o A decentralized network model, the concept behind much of the

information revolution, shares data horizontally too. Agencies would

still have their own databases, but those databases would be searchable

across agency lines. In this system, secrets are protected through the

design of the network and an "information rights management" approach

that controls access to the data, not access to the whole net- work.An

outstanding conceptual framework for this kind of "trusted information

network" has been developed by a task force of leading professionals in

national security, information technology, and law assembled by the

Markle Foundation. Its report has been widely dis- cussed throughout the

U.S. government, but has not yet been con-

verted into action.17

Recommendation: The

president should lead the government-wide effort to bring the major

national security institutions into the infor- mation revolution. He

should coordinate the resolution of the legal, policy, and technical

issues across agencies to create a "trusted infor-

mation network."

o No one agency can do it

alone. Well-meaning agency officials are

under tremendous pressure to update their systems. Alone, they may only

be able to modernize the stovepipes, not replace them.

o Only presidential leadership can develop government-wide concepts

and standards. Currently, no one is doing this job. Backed by the Office

of Management and Budget, a new National Intelligence Director empowered

to set common standards for information use throughout the community,

and a secretary of homeland security who helps

HOW TO DO IT? 419

extend the system to

public agencies and relevant private-sector data- bases, a

government-wide initiative can succeed.

o White House leadership is also needed because the policy and legal

issues are harder than the technical ones. The necessary technology

already exists. What does not are the rules for acquiring, accessing,

sharing, and using the vast stores of public and private data that may

be available. When information sharing works, it is a powerful tool.

Therefore the sharing and uses of information must be guided by a set of

practical policy guidelines that simultaneously empower and constrain

officials, telling them clearly what is and is not permitted.

"This is government

acting in new ways, to face new threats," the most recent Markle report

explains."And while such change is necessary, it must be accomplished

while engendering the people's trust that privacy and other civil

liberties are being protected, that businesses are not being unduly

burdened with requests for extraneous or useless information, that

taxpayer money is being well spent, and that, ultimately, the network

will be effective in protect- ing our security."The authors add:

"Leadership is emerging from all levels of government and from many

places in the private sector.What is needed now is a plan to accelerate

these efforts, and public debate and consensus on the

goals."18

13.4 UNITY OF EFFORT IN

THE CONGRESS

Strengthen Congressional

Oversight of Intelligence and Homeland

Security

Of all our recommendations, strengthening congressional oversight may be

among the most difficult and important. So long as oversight is governed

by current congressional rules and resolutions, we believe the American

people will not get the security they want and need.The United States

needs a strong, stable, and capable congressional committee structure to

give America's national intelligence agencies oversight, support, and

leadership.

Few things are more difficult to change in Washington than congressional

committee jurisdiction and prerogatives. To a member, these assignments

are almost as important as the map of his or her congressional

district.The Amer- ican people may have to insist that these changes

occur, or they may well not happen. Having interviewed numerous members

of Congress from both par- ties, as well as congressional staff members,

we found that dissatisfaction with congressional oversight remains

widespread.

The future challenges of America's intelligence agencies are

daunting.They include the need to develop leading-edge technologies that

give our policy-

420 THE 9/11 COMMISSION

REPORT

makers and warfighters a

decisive edge in any conflict where the interests of the United States

are vital. Not only does good intelligence win wars, but the best

intelligence enables us to prevent them from happening altogether.

Under the terms of existing rules and resolutions the House and Senate

intelligence committees lack the power, influence, and sustained

capability to meet this challenge.While few members of Congress have the

broad knowl- edge of intelligence activities or the know-how about the

technologies employed, all members need to feel assured that good

oversight is happening. When their unfamiliarity with the subject is

combined with the need to pre- serve security, a mandate emerges for

substantial change.

Tinkering with the existing structure is not sufficient. Either Congress

should create a joint committee for intelligence, using the Joint Atomic

Energy Committee as its model, or it should create House and Senate

committees with combined authorizing and appropriations powers.

Whichever of these two forms are chosen, the goal should be a structure-

codified by resolution with powers expressly granted and carefully

limited- allowing a relatively small group of members of Congress, given

time and reason to master the subject and the agencies, to conduct

oversight of the intel- ligence establishment and be clearly accountable

for their work. The staff of this committee should be nonpartisan and

work for the entire committee and not for individual members.

The other reforms we have suggested-for a National Counterterrorism

Center and a National Intelligence Director-will not work if

congressional oversight does not change too. Unity of effort in

executive management can be lost if it is fractured by divided

congressional oversight.

Recommendation:

Congressional oversight for intelligence-and counterterrorism-is now

dysfunctional. Congress should address this problem.We have considered

various alternatives: A joint committee on the old model of the Joint

Committee on Atomic Energy is one. A single committee in each house of

Congress, combining authoriz- ing and appropriating authorities, is

another.

o The new committee or

committees should conduct continuing stud-

ies of the activities of the intelligence agencies and report problems

relating to the development and use of intelligence to all members of

the House and Senate.

o We have already recommended that the total level of funding for intel-

ligence be made public, and that the national intelligence program be

appropriated to the National Intelligence Director, not to the secre-

tary of defense.19

HOW TO DO IT? 421

We also recommend that

the intelligence committee should have a

subcommittee specifically dedicated to oversight, freed from the con-

suming responsibility of working on the budget.

o The resolution creating the new intelligence committee structure

should grant subpoena authority to the committee or committees. The

majority party's representation on this committee should never exceed

the minority's representation by more than one.

o Four of the members appointed to this committee or committees

should be a member who also serves on each of the following addi- tional

committees:Armed Services, Judiciary, Foreign Affairs, and the Defense

Appropriations subcommittee. In this way the other major congressional

interests can be brought together in the new commit- tee's work.

o Members should serve indefinitely on the intelligence committees,

without set terms, thereby letting them accumulate expertise.

o The committees should be smaller-perhaps seven or nine members

in each house-so that each member feels a greater sense of respon-

sibility, and accountability, for the quality of the committee's work.

The leaders of the

Department of Homeland Security now appear before 88 committees and

subcommittees of Congress. One expert witness (not a mem- ber of the

administration) told us that this is perhaps the single largest obstacle

impeding the department's successful development.The one attempt to con-

solidate such committee authority, the House Select Committee on Home-

land Security, may be eliminated.The Senate does not have even this.

Congress needs to establish for the Department of Homeland Security the

kind of clear authority and responsibility that exist to enable the

Justice Depart- ment to deal with crime and the Defense Department to

deal with threats to national security.Through not more than one

authorizing committee and one appropriating subcommittee in each house,

Congress should be able to ask the secretary of homeland security

whether he or she has the resources to provide reasonable security

against major terrorist acts within the United States and to hold the

secretary accountable for the department's performance.

Recommendation: Congress

should create a single, principal point of oversight and review for

homeland security. Congressional leaders are best able to judge what

committee should have jurisdiction over this department and its duties.

But we believe that Congress does have the obligation to choose one in

the House and one in the Senate, and that this committee should be a

permanent standing committee with a nonpartisan staff.

422 THE 9/11 COMMISSION

REPORT

Improve the Transitions

between Administrations

In chapter 6, we described the transition of 2000-2001. Beyond the

policy issues we described, the new administration did not have its

deputy cabinet offi- cers in place until the spring of 2001, and the

critical subcabinet officials were not confirmed until the summer-if

then. In other words, the new adminis- tration-like others before it-did

not have its team on the job until at least six months after it took

office.

Recommendation: Since a

catastrophic attack could occur with lit- tle or no notice, we should

minimize as much as possible the disrup- tion of national security

policymaking during the change of administrations by accelerating the

process for national security appointments. We think the process could

be improved significantly so transitions can work more effectively and

allow new officials to assume their new responsibilities as quickly as

possible.

o Before the election,

candidates should submit the names of selected

members of their prospective transition teams to the FBI so that, if

necessary, those team members can obtain security clearances imme-

diately after the election is over.

o A president-elect should submit lists of possible candidates for

national security positions to begin obtaining security clearances

immediately after the election, so that their background investigations

can be complete before January 20.

o A single federal agency should be responsible for providing and main-

taining security clearances, ensuring uniform standards-including

uniform security questionnaires and financial report requirements, and

maintaining a single database.This agency can also be responsible for

administering polygraph tests on behalf of organizations that require

them.

o A president-elect should submit the nominations of the entire new

national security team, through the level of under secretary of cabi-

net departments, not later than January 20. The Senate, in return,

should adopt special rules requiring hearings and votes to confirm or

reject national security nominees within 30 days of their submission.

The Senate should not require confirmation of such executive appointees

below Executive Level 3.

o The outgoing administration should provide the president-elect, as

soon as possible after election day, with a classified, compartmented

list that catalogues specific, operational threats to national security;

major military or covert operations; and pending decisions on the pos-

HOW TO DO IT? 423

sible use of force. Such

a document could provide both notice and a checklist, inviting a

president-elect to inquire and learn more.

13.5 ORGANIZING AMERICA'S

DEFENSES IN THE

UNITED STATES

The Future Role of the

FBI

We have considered proposals for a new agency dedicated to intelligence

col- lection in the United States. Some call this a proposal for an

"American MI- 5," although the analogy is weak-the actual British

Security Service is a relatively small worldwide agency that combines

duties assigned in the U.S. government to the Terrorist Threat

Integration Center, the CIA, the FBI, and the Department of Homeland

Security.

The concern about the FBI is that it has long favored its criminal

justice mission over its national security mission. Part of the reason

for this is the demand around the country for FBI help on criminal

matters. The FBI was criticized, rightly, for the overzealous domestic

intelligence investigations dis- closed during the 1970s.The pendulum

swung away from those types of inves- tigations during the 1980s and

1990s, though the FBI maintained an active counterintelligence function

and was the lead agency for the investigation of foreign terrorist

groups operating inside the United States.

We do not recommend the creation of a new domestic intelligence agency.

It is not needed if our other recommendations are adopted-to establish a

strong national intelligence center, part of the NCTC, that will oversee

coun- terterrorism intelligence work, foreign and domestic, and to

create a National Intelligence Director who can set and enforce

standards for the collection, pro- cessing, and reporting of

information.

Under the structures we recommend, the FBI's role is focused, but still

vital. The FBI does need to be able to direct its thousands of agents

and other employees to collect intelligence in America's cities and

towns-interviewing informants, conducting surveillance and searches,

tracking individuals, work- ing collaboratively with local authorities,

and doing so with meticulous atten- tion to detail and compliance with

the law.The FBI's job in the streets of the United States would thus be

a domestic equivalent, operating under the U.S. Constitution and quite

different laws and rules, to the job of the CIA's opera- tions officers

abroad.

Creating a new domestic intelligence agency has other drawbacks.

o The FBI is accustomed

to carrying out sensitive intelligence collec-

tion operations in compliance with the law. If a new domestic intel-

ligence agency were outside of the Department of Justice, the process of

legal oversight-never easy-could become even more difficult.

424 THE 9/11 COMMISSION

REPORT

Abuses of civil liberties

could create a backlash that would impair the collection of needed

intelligence.

o Creating a new domestic intelligence agency would divert attention

of the officials most responsible for current counterterrorism efforts

while the threat remains high. Putting a new player into the mix of

federal agencies with counterterrorism responsibilities would exacer-

bate existing information-sharing problems.

o A new domestic intelligence agency would need to acquire assets and

personnel.The FBI already has 28,000 employees; 56 field offices, 400

satellite offices, and 47 legal attaché offices; a laboratory,

operations center, and training facility; an existing network of

informants, coop- erating defendants, and other sources; and

relationships with state and local law enforcement, the CIA, and foreign

intelligence and law enforcement agencies.

o Counterterrorism investigations in the United States very quickly

become matters that involve violations of criminal law and possible law

enforcement action. Because the FBI can have agents working criminal

matters and agents working intelligence investigations con- cerning the

same international terrorism target, the full range of inves- tigative

tools against a suspected terrorist can be considered within one agency.

The removal of "the wall" that existed before 9/11 between intelligence

and law enforcement has opened up new opportunities for cooperative

action within the FBI.

o Counterterrorism investigations often overlap or are cued by other

criminal investigations, such as money laundering or the smuggling of

contraband. In the field, the close connection to criminal work has many

benefits.

Our recommendation to

leave counterterrorism intelligence collection in the United States with

the FBI still depends on an assessment that the FBI-if it makes an

all-out effort to institutionalize change-can do the job.As we men-

tioned in chapter 3, we have been impressed by the determination that

agents display in tracking down details, patiently going the extra mile

and working the extra month, to put facts in the place of speculation.

In our report we have shown how agents in Phoenix, Minneapolis, and

NewYork displayed initiative in pressing their investigations.

FBI agents and analysts in the field need to have sustained support and

ded- icated resources to become stronger intelligence officers. They

need to be rewarded for acquiring informants and for gathering and

disseminating infor- mation differently and more broadly than usual in a

traditional criminal inves-

HOW TO DO IT? 425

tigation. FBI employees

need to report and analyze what they have learned in ways the Bureau has

never done before.

Under Director Robert Mueller, the Bureau has made significant progress

in improving its intelligence capabilities. It now has an Office of

Intelligence, overseen by the top tier of FBI management. Field

intelligence groups have been created in all field offices to put FBI

priorities and the emphasis on intel- ligence into practice. Advances

have been made in improving the Bureau's information technology systems

and in increasing connectivity and informa- tion sharing with

intelligence community agencies.

Director Mueller has also recognized that the FBI's reforms are far from

complete. He has outlined a number of areas where added measures may be

necessary. Specifically, he has recognized that the FBI needs to recruit

from a broader pool of candidates, that agents and analysts working on

national secu- rity matters require specialized training, and that

agents should specialize within programs after obtaining a generalist

foundation.The FBI is developing career tracks for agents to specialize

in counterterrorism/counterintelligence, cyber crimes, criminal

investigations, or intelligence. It is establishing a program for

certifying agents as intelligence officers, a certification that will be

a prerequi- site for promotion to the senior ranks of the Bureau. New

training programs have been instituted for intelligence-related

subjects.

The Director of the FBI has proposed creating an Intelligence

Directorate as a further refinement of the FBI intelligence program.This

directorate would include units for intelligence planning and policy and

for the direction of ana- lysts and linguists.

We want to ensure that the Bureau's shift to a preventive

counterterrorism posture is more fully institutionalized so that it

survives beyond Director Mueller's tenure.We have found that in the past

the Bureau has announced its willingness to reform and restructure

itself to address transnational security threats, but has fallen

short-failing to effect the necessary institutional and cul- tural

changes organization-wide.We want to ensure that this does not happen

again. Despite having found acceptance of the Director's clear message

that counterterrorism is now the FBI's top priority, two years after

9/11 we also found gaps between some of the announced reforms and the

reality in the field. We are concerned that management in the field

offices still can allocate peo- ple and resources to local concerns that

diverge from the national security mis- sion.This system could revert to

a focus on lower-priority criminal justice cases over national security

requirements.

Recommendation: A

specialized and integrated national security workforce should be

established at the FBI consisting of agents, ana- lysts, linguists, and

surveillance specialists who are recruited, trained, rewarded, and

retained to ensure the development of an institutional

426 THE 9/11 COMMISSION

REPORT

culture imbued with a

deep expertise in intelligence and national security.

o The president, by

executive order or directive, should direct the FBI

to develop this intelligence cadre.

o Recognizing that cross-fertilization between the criminal justice and

national security disciplines is vital to the success of both missions,

all new agents should receive basic training in both areas. Furthermore,

new agents should begin their careers with meaningful assignments in

both areas.

o Agents and analysts should then specialize in one of these disciplines

and have the option to work such matters for their entire career with

the Bureau. Certain advanced training courses and assignments to other

intelligence agencies should be required to advance within the national

security discipline.

o In the interest of cross-fertilization, all senior FBI managers,

includ-

ing those working on law enforcement matters, should be certified

intelligence officers.

o The FBI should fully implement a recruiting, hiring, and selection

process for agents and analysts that enhances its ability to target and

attract individuals with educational and professional backgrounds in

intelligence, international relations, language, technology, and other

relevant skills.

o The FBI should institute the integration of

analysts,agents,linguists,and

surveillance personnel in the field so that a dedicated team approach is

brought to bear on national security intelligence operations.

o Each field office should have an official at the field office's deputy

level

for national security matters.This individual would have management

oversight and ensure that the national priorities are carried out in the

field.

o The FBI should align its budget structure according to its four main

programs-intelligence, counterterrorism and counterintelligence,

criminal, and criminal justice services-to ensure better transparency on

program costs, management of resources, and protection of the

intelligence program.20

o The FBI should report regularly to Congress in its semiannual pro-

gram reviews designed to identify whether each field office is appro-

priately addressing FBI and national program priorities.

HOW TO DO IT? 427

o The FBI should report

regularly to Congress in detail on the qualifi-

cations, status, and roles of analysts in the field and at headquarters.

Congress should ensure that analysts are afforded training and career

opportunities on a par with those offered analysts in other intelligence

community agencies.

o The Congress should make sure funding is available to accelerate the

expansion of secure facilities in FBI field offices so as to increase

their ability to use secure email systems and classified intelligence

product exchanges. The Congress should monitor whether the FBI's

information-sharing principles are implemented in practice.

The FBI is just a small

fraction of the national law enforcement commu- nity in the United

States, a community comprised mainly of state and local agencies.The

network designed for sharing information, and the work of the FBI

through local Joint Terrorism Task Forces, should build a reciprocal

rela- tionship, in which state and local agents understand what

information they are looking for and, in return, receive some of the

information being developed about what is happening, or may happen, in

their communities. In this rela- tionship, the Department of Homeland

Security also will play an important part.

The Homeland Security Act of 2002 gave the under secretary for informa-

tion analysis and infrastructure protection broad responsibilities. In

practice, this directorate has the job to map "terrorist threats to the

homeland against our assessed vulnerabilities in order to drive our

efforts to protect against terrorist threats."21 These capabilities are

still embryonic. The directorate has not yet developed the capacity to

perform one of its assigned jobs, which is to assim- ilate and analyze

information from Homeland Security's own component agencies, such as the

Coast Guard, Secret Service, Transportation Security Administration,

Immigration and Customs Enforcement, and Customs and Border

Protection.The secretary of homeland security must ensure that these

components work with the Information Analysis and Infrastructure

Protection

Directorate so that this office can perform its mission.22

Homeland Defense

At several points in our inquiry, we asked, "Who is responsible for

defending us at home?" Our national defense at home is the

responsibility, first, of the Department of Defense and, second, of the

Department of Homeland Secu-

rity.They must have clear delineations of responsibility and authority.

We found that NORAD, which had been given the responsibility for

defending U.S. airspace, had construed that mission to focus on threats

com- ing from outside America's borders. It did not adjust its focus

even though the intelligence community had gathered intelligence on the

possibility that ter-

428 THE 9/11 COMMISSION

REPORT

rorists might turn to

hijacking and even use of planes as missiles.We have been assured that

NORAD has now embraced the full mission. Northern Com- mand has been

established to assume responsibility for the defense of the domestic

United States.

Recommendation: The

Department of Defense and its oversight committees should regularly

assess the adequacy of Northern Com- mand's strategies and planning to

defend the United States against military threats to the homeland.

The Department of

Homeland Security was established to consolidate all of the domestic

agencies responsible for securing America's borders and national

infrastructure, most of which is in private hands. It should identify

those elements of our transportation, energy, communications, financial,

and other institutions that need to be protected, develop plans to

protect that infra- structure, and exercise the mechanisms to enhance

preparedness. This means going well beyond the preexisting jobs of the